The interior of southern Norway offers spectacular hiking opportunities. Dense, mixed forests are intersected by babbling brooks. Tranquil marshy pools dot the landscape and give home to a wide array of waterfowl. A lucky wanderer may spot both deer and the imposing, though mostly harmless elk. But what is idyllic in the daytime, takes on a distinctly more sinister atmosphere once darkness falls. Crooked tree trunks and jutting rock formations seem to come alive as other-worldly entities. In pools of water, the Nixie lives. This eerie environment has given birth to Norway’s long tradition of enchanting fairy tales. The English (or rather Scottish) word “eldritch” is in Norwegian perhaps best rendered as “trolsk” – literally “troll-ish”.

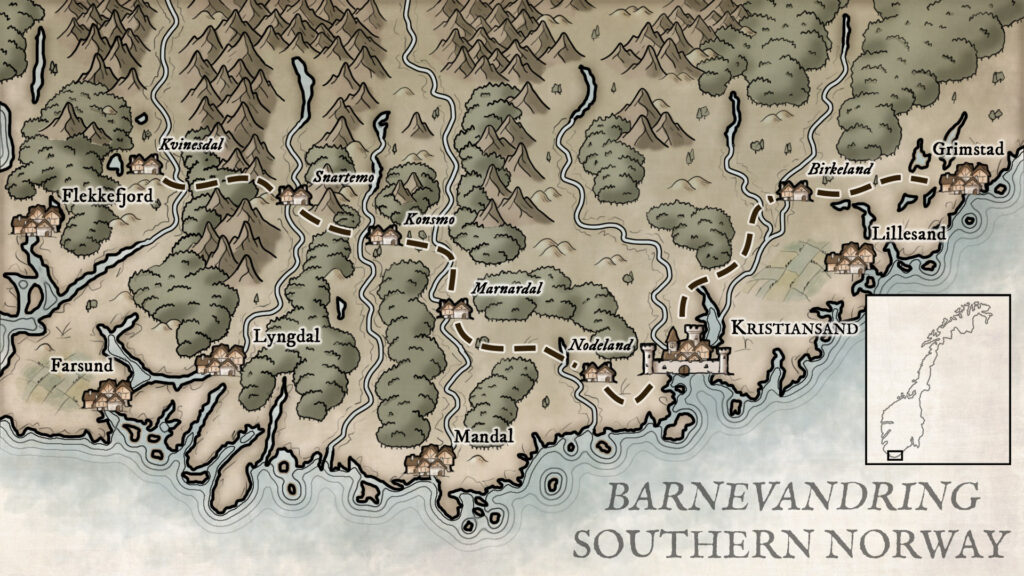

It was through this landscape that, in 1836, Even Reiersen Fidje set out from his home farm of West Fidje near Marnardal, for Fjære, just east of Grimstad. The journey, of over 100 kilometres, was made on foot. Even was ten years old at the time. He was one of around 3,000 children who made similar journeys in the years from 1830 to 1900 in a movement known as the children’s work migration, or barnevandringen.

The western part of Agder, the southernmost region of Norway, is dominated by mountainous terrain reaching all the way to the coast. Subsistence here has been dominated by fishing and trade along the coast, while in the narrow, glacial valleys inland, people have carved out a living on the alluvial plains along the rivers. The landscape opens up towards the east, where farming and husbandry on a larger scale is possible. For this reason, as the demographic transition began to take hold and the population grew, many western families chose to send their sons and daughters east for employment during the summer months. Here they were normally set to herd livestock; a job even the smallest children could perform. The trek, though, was both exhausting and dangerous, involving stages of up to sixty kilometres a day. Older children sometimes had to carry their younger siblings on their backs when their little legs would carry them no further. Bad weather could overtake the wanderers at any time, and often they were forced to sleep outdoors, taking shelter wherever they found it. The forests held great dangers, from wolfs and bears to equally predatory human beings. From time to time, farmers along the way might take pity on the little ones and offer them food and a roof to sleep under. Testimony survives, however, from those listening to the heart-breaking sound of the youngest children crying as they had to walk on the next day.

Much like childhood itself, its history was long a neglected topic. The pioneer within the field was the French historian Philippe Ariès, who in 1960 published the book known in English as Centuries of Childhood. Here, Ariès tells the story of an Italian visitor to England in the late fifteenth century who was shocked by the custom of sending children into service outside the home, often as early as seven to nine years of age. He concluded from this that the English must have had a certain “want of affection” for their offspring.[1] Two things become clear from this anecdote: that service or apprenticeship for young children was common at least from the late Middle Ages, and that it was more common in Northern than in Southern Europe.

Other historians, such as Colin Haywood and Nicholas Orme, have followed in the path cleared by Ariès, and the topic of service is always inescapable: its psychological, sociological and economic effects.[2] No one has quite understood its significance to European society, however, like the Danish historian Patricia Crone. Crone was not a specialist on European history; her studies centred on the origins of Islam. Perhaps it was this outside perspective that allowed her to see that what had been missed, was how much the custom set Europe apart from the rest of the world. In Europe, Crone wrote in her 1989 Pre-Industrial Societies, commoners married later than elsewhere, and young people had to leave their homes to accumulate funds to form families of their own. This contrasted with the norm in other parts of the world, where children remained part of their native “landholding corporation” until they could be married off, preferably at an early age. European late marriages, on the other hand, gave the spouses themselves greater autonomy in choice of partner. European individualism has been credited to such factors as urbanisation, institutions like guilds and universities, and the fragmented nature of European politics. But just as important may have been the break-up of the nuclear family, and a pattern of late marriages; factors that combined to develop a spirit of individuality that was unique in the world.[3]

By the nineteenth century, however, the social consequences of child labour were becoming a concern to European governments. In the 1850s, the Norwegian parliament gave a grant to the sociologist Eilert Sundt for the study of the nation’s poor. Sundt is widely considered the greatest Norwegian social scientist of all time; a Norwegian Malthus, if you like, but without the latter’s fatal errors on these exact topics of marriage patterns and sustainability. Sundt’s focus was not on some God’s eye view of the causes behind poverty, but rather on understanding poverty’s effect on poor people themselves. Born in Agder, in the coastal town of Farsund, Sundt knew the people and places of southern Norway well.

What Sundt found was surprising. Rather than the poorest, most destitute families sending their children into service, it was those of middling wealth who were most likely to do so. Children of families that were “on the county” were rarely found among the work migrants, and those who went were likely to return before time. Those who served out their period of contract were able to put aside money for later life, and gained a good understanding of personal finance, as well as useful work experience.[4] His recommendation was for the government not to intervene, as he found the practice beneficial. When, a century and a half later, local historian Paul Sveinall made a systematic study of barnevandringen, he found much the same thing. Collecting data on around 500 of the child migrants, he concluded that the children had generally done well later in life, and that their life expectancy was above the national average. Based on interviews with descendants, it became clear that these migrating labourers took great pride in their experience, and what it had taught them.[5]

What eventually ended barnevandring in Norway, as it ended child labour all over Europe, was the enforcement of universal, mandatory primary education. This was undoubtedly a good thing for the children involved; it allowed them more time for play and for socialising with their peers, as well as the opportunity to develop a more versatile set of skills. It was also beneficial for society as a whole; a more diversified economy could now draw talent from a wider section of the population to fill a growing number of non-agricultural jobs. But to view child labour only under the aspect of exploitation and suffering is too simplistic. When we think of child labour today, what comes to mind tends to be the quite horrific conditions of factory or mining work from the early years of the Industrial Revolution. This, however, was only a brief episode in human history of about a century – give or take a few decades depending on the nation in question. In reality, the norm in all human societies since the dawn of history has been for children to enter the work force as soon as they were able to do so. Archaeological excavations from the stone age have turned up examples of the production of stone tools – so-called “flintknapping” – where the learning process of a child is evident from the quality of the work.[6] For most of human history, work was simply how children developed their individual agency and acquired the skills needed to survive and prosper.

This was certainly the case with Even Reiersen Fidje, the 10-year-old from the opening of this text. When he left home to find service elsewhere, it was on his own initiative, against the advice of his parents (particularly, as can be imagined, his mother). Having taught himself to read at an early age, he found little challenge in school, and wanted to get out in the world and make his own fortune. His host family, however, recognised the boy’s aptitude and recommended he continue on the academic path. So he did, and later became a teacher himself, before entering into politics. From 1871 to 1888, he served as member of the Storting – the Norwegian parliament. When Eilert Sundt travelled around Agder in the 1850s to collect data for his research, he did so in the company of his good friend, former barnevandrer Even Reiersen Fidje.[7]

CB

Christian IV of Denmark-Norway, known for his involvement in the Thirty Years’ War, founded a number of cities in his sixty-year reign. Like Alexander the Great, he liked to name them after himself, so when in 1641 he established a city on the sandy grounds at the mouth of the river Otra, he named it Christianssand. In 1682, the bishop’s see was moved here, and a cathedral was erected. Twice the church has been consumed by fire, and the current cathedral, built in 1885, is the third of its kind.

Though the name of the city has today been Norwegianised into Kristiansand, the local brewery kept the original spelling in its name. Christianssands Bryggeri – or CB – started production in 1859. Legend has it that in 1932, during a particularly dry summer, the company plumber offered to search for water using a divining rod. What he found was an unfailing well of crystal-clear, cool groundwater. For 90 years, this well was the foundation on which the identity of the brand was built. It made for a mild, simple pilsner, that went perfectly with seafood in the long, sunlit summer nights of southern Norway. This, however, mattered little to the brewery’s new owners, who in 2022 decided to move production. Away from Kristiansand, and away from its well.

[1] Philippe Ariès, Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life (New York: Vintage Books, 1962), 365.

[2] Colin Heywood, A History of Childhood: Children and Childhood in the West from Medieval to Modern Times (Cambridge, UK; Malden, Mass: Polity Press, 2001), 116–28; Nicholas Orme, Medieval Children (New Haven, Conn. London: Yale University Press, 2003), 310–21.

[3] Patricia Crone, Pre-Industrial Societies, New Perspectives on the Past (Oxford, UK ; Cambridge, MA, USA: B. Blackwell, 1989), 152–5.

[4] Eilert Sundt, Husfliden i Norge (Oslo: Blix Forlag, 1945 [1867]), 130.

[5] Paul Sveinall, Ut, Opp Og Fram – Barnevandringen På Agder 1720-1920 (Agder, 2021), 84–85.

[6] April Nowell, Growing up in the Ice Age: Fossil and Archaeological Evidence of the Lived Lives of Plio-Pleistocene Children (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2021), 79-92.

[7] Sveinall, Opp, Ut Og Fram, 24, 113-14.