A man walks the streets of Bruges at night. He is a widower these past five years. When his wife died he moved here, since this city, like his wife, is dead. Evening after evening he spends wandering aimlessly along the grey, deserted streets, thinking of death, of the dead. On one such night, walking ahead of him on the pavement, he sees his wife. It is not her, of course, but the resemblance is so striking that he cannot help but follow the young woman to discover her identity. He becomes enamoured with this doppelgänger, and since it is his wife whom he sees in her, he cannot truly be said to betray the memory of the deceased. Slowly he falls into an unhealthy obsession, deeper and deeper, with no apparent escape.

This is the plot of George Rodenbach’s gothic novel Bruges-la-Morte, written in 1891. The title is difficult to translate, since it is somewhat cryptic also in the original French. Death in the abstract is la mort in French; la Morte – capitalised in the title – means the dead woman. A passage of the novel provides more insight: “Bruges was his dead wife. His dead wife was Bruges. Everything was united in a similar destiny. It was Bruges-la-Morte.” (Ch. II)

Rodenbach was not the first to write about the dangers of letting our lives be consumed by the dead; this has been a theme of literature from the Orpheus legend to Wuthering Heights to Beloved. Nor is he the only one who has noticed the special character of Bruges as a city frozen in time; this is an impression noted by authors as diverse as Wordsworth (“A deeper peace than that in deserts found!”), Longfellow (“Silence, silence everywhere,”), Baudelaire (“It smells like death”), Zweig (“The streets are empty, as after a feast”) and Henry Miller (“I am still uncertain as to whether I am dreaming or wide awake”).[1]

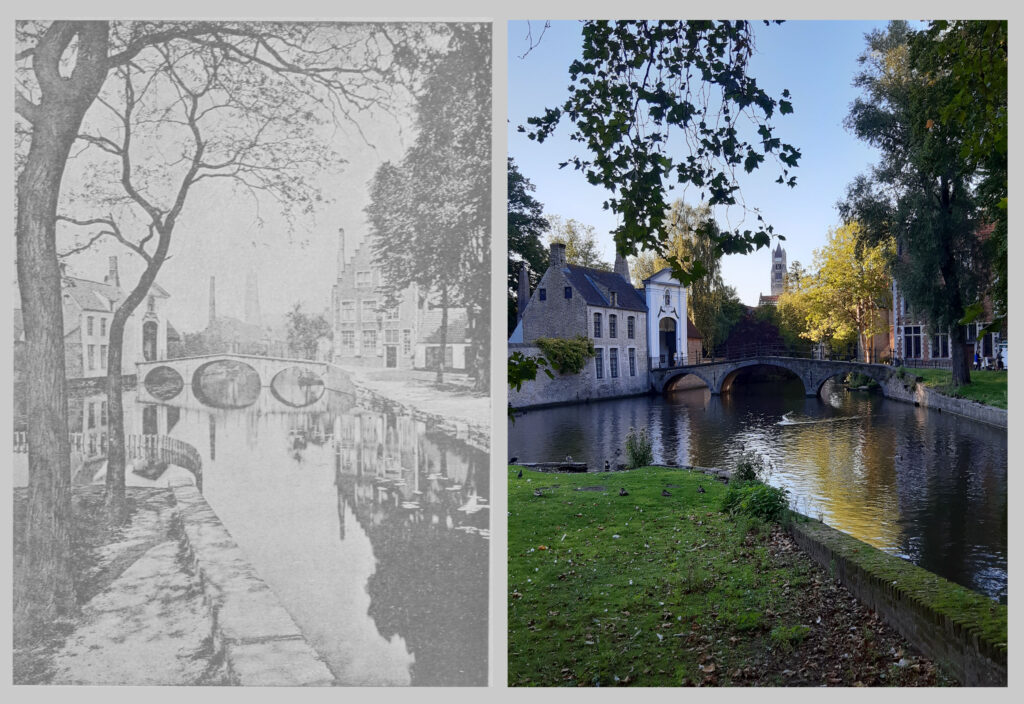

What is truly innovative in Rodenbach’s novel, is his use of photography. Liberally sprinkled throughout the book are pictures he himself took of the city. Experimenting with this still relatively new medium, the author was interested in how photographs could be used to complement the words. In general, the photos do not directly illustrate the text, but help enhance the general mood of the story told. In Rodenbach’s dull, greyscale photos, the streets are almost always empty, adding to the novel’s eerie, ghostlike atmosphere.

To anyone visiting Bruges today, the city seems far from dead; the streets are bustling with people, sounds and sights. The Quai du Rosaire (Rozenhoedkaai in Flemish), where Rodenbach’s tragic hero Hugues had set up his morbid residence, is one of the most picturesque spots in the city. Here people line up to take pictures of the ancient brickwork buildings, while swan couples swim languidly by on the encircling canal. The marketplace is also teeming with life, in between the various stalls in the shadow of the 83-metre-high Belfry of Bruges. Like the city itself, it is on the UNESCO World Heritage list.

There is something to admire around every corner, and yet, something feels a little off about this place. Look and listen, and you find that almost everyone you meet is a tourist. You will struggle to find a shop that sells anything but trinkets and souvenirs. Then, in the evening, once the day-trippers have gone, the streets revert to emptiness, and you see the city as Rodenbach captured it in words and pictures: dead.

What is a dead city? First of all, we should distinguish between different types of cities that may appear to our eyes as if passed from time to eternity. We may speak of three, by no means impermeable, categories: the preserved, the moved, and the truly dead cities.

Throughout history, there has been little impulse to preserve architecture for its own sake. Progress has tended to take precedence. Antiquarianism, the idea that ancient artifacts have a value of their own, really only dates back to the sixteenth century, and concerted efforts to preserve old buildings are of an even newer date. Rulers and city-planners have been more than happy when circumstances have given them the opportunity to make a fresh start, as Nero after the burning of Rome, Charles II and Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of London, and Napoleon III and Georges-Eugène Haussmann after the 1848 Revolution in Paris.

There have, however, been some exceptions. These are cases where a city’s identity is so closely tied to its buildings that they become sacrosanct, and shielded from destruction. Cambridge, England, accommodates one of the foremost universities in the world. It is a thriving, prosperous city, with constant building activity to house a wide range of groundbreaking research facilities. Yet the centre remains remarkably well-preserved, where its medieval origin is still evident along the main street. It is as if the stones themselves contain the knowledge and wisdom of centuries.

Santiago de Compostela in Spain became one of the main pilgrimage destinations in Europe after it claimed the remains of Saint James the Greater in the ninth century. This has been the city’s main attraction ever since, and its various convents, hospitals and palaces, centred around the twelfth-century cathedral, have been immune to modernisation. The whole city has become a relic, but it still meets the requirement for which it was built: to house a saint and welcome pilgrims.

Then there is the Eternal City itself: Rome. Certainly, during periods of the city’s decline, stones would be pilfered from the Colosseum for other uses, but what is remarkable is how much of its ancient, medieval and baroque buildings remain. Even after it became Italy’s capital in 1871, and grew more than tenfold, this did not change.

Another category of dead cities is those that, for purely practical reasons, have had to somewhat shift their centre. Particularly in the south of Europe, during the times of barbarian invasions in the Dark Ages, cities were often located on hilltops that offered natural defence against invaders. Once the threat subsided into the modern era, this became impractical, and the population expanded unto the plains below. The city of Bergamo is laid out in rectilinear grids with broad boulevards. It is served by an international airport and boasts a renowned football team. But up above, accessible by a funicolare, lies the medieval city as if untouched by time.

An even more instructive example can be found on the island of Malta. The island nation’s former capital, which unlike coastal Valletta is located inland, is known colloquially as “The Silent City”. There is indeed a ghostly atmosphere to the narrow streets between limestone houses in this small, fortified city on a hill. Interestingly, its official name is Mdina, which in the Arabic-derived Maltese means “city”, while the sprawling suburb below is called Rabat, Arabic for “suburb”.

Finally, there are the true dead cities. These are the ones that, for one reason or another, no longer serve the purpose for which they emerged, and have gone into decline. The best-known example is probably Venice. Their near-monopoly on trade between Europe and the Orient granted the city centuries of unprecedented power and prosperity. But the combined factors of Ottoman intransigence and alternative sea routes to the east led to the city’s decline. This did not happen overnight, but eventually Venice became a museum city.

The city of Toledo, on the other hand, had its destiny sealed quite abruptly when, in 1561, Philip II of Spain moved the nation’s capital to Madrid. Without the royal court, Toledo lost the central position it had held under both Muslim and Christian rulers.

And then there is Bruges. In 1134, a powerful tidal surge hit the coast of the Low Countries and created the inlet of Zwin. This natural disaster was a blessing for the small town, since it now had a direct connection to the sea. During the commercial revolution of the High Middle Ages, Bruges became the leading port of north-western Europe; merchants from the Hansa cities, Genoa and Venice would all harbour here to trade.[2] But the good fortune did not last.

In 1340, the greatest naval battle of the Hundred Years’ War took place at Sluys, just to the north-east of Bruges. Such a battle could have been fought today, not only because the relations between England and France have improved, but because the site of the battle is now solid ground. There were no major rivers feeding into the Zwin, and almost as soon as it had been created, it began silting up again. Over the centuries, several measures were tried to keep the waterways open, at enormous public expense. Eventually, however, the city’s struggle against the forces of nature was destined to fail. By around 1560, Antwerp had taken over the role as the regional centre of trade.[3] Bruges was left behind, a harbour city without a harbour. It had become, quite literally, a backwater.

In the cynical view, the dead cities of Europe have ended up as theatre sets; empty scaffolding kept on life support for the hordes of mass tourism to take their photos, post online, tick off a box – little better than Disneyland. And yet, what a blessing it is to have these remnants of the past right in our midst; to experience history not only through words and artifacts, but through the very environment wherein it was lived. No other part of the world has a continuous history documented architecturally in such a countless number of places, from the smallest village to the largest metropolis.

And then again, are these cities really dead? Their inhabitants are not. People here live their lives as they have for centuries; many work in hospitality, others in business, administration, education or health care. To them, the houses are homes, buildings are workplaces, streets are their commute. Here, in Faulkner’s words, the past is never dead, it’s not even past.

We are conditioned to associate vitality with constant architectural renewal, and the lack thereof with decay. But one could just as easily argue that the cities that sever all links with their history are the ones deprived of life. With no connection to the past they go about their lives without purpose, untethered, as orphans, amnesiacs, zombies.

Rainer Maria Rilke saw what those other writers saw in Bruges: a city past its prime. But he was also able to see beyond this: that life goes on, for those who know where to look. In a poem fittingly titled “Quai du Rosaire (Bruges)”, he writes:

then suddenly, behind bright, glowing windows

the dancers twirl inside the estaminets.[4]

If you ever find yourself in one of these dead cities, wait until the tourists have left or retired to their hotels. Wander around like Rodenbach’s Hugues, avoiding the grand squares and broad streets. Turn a corner and get lost in narrow alleyways. If you are lucky, you might stumble upon a crowd of locals, enjoying themselves with music, food and drink. And if, in that crowd, you were to see the face of a long-dead loved one, be thankful, and move on.

Brugse Zot

Bruges City Hall, built 1376-1421, is one of the oldest in the Low Countries. Both the inside and outside are stunningly ornate with gothic decorations. It is situated on the Burg Square – so called because it used to be a fortress – and immediately to its right lies the Basilica of the Holy Blood. This church claims to possess a vial of the true blood of Christ. At certain times of the day, visitors can file by one after one to where a nun will lift a piece of cloth and reveal the relic.

De Halve Maan (The Half Moon) has brewed beer in the centre of Bruges since 1856, though the site has housed a brewery for five centuries. Originally, bottles were transported by horse and cart through the city, but as demand increased, the brewery opened a separate bottling plant outside of town. To avoid damage to the narrow, cobbled streets, a pipeline was constructed from the brewery to the bottling plant. In 2016, the 3.3 km beer line was opened, unique of its kind in the world. One of its beer carries with it a piece of local lore. According to legend, when the citizens petitioned Emperor Maximilian I (1508-1519) for the right to construct an insane asylum, he suggested they simply close the city gates, and they would have their madhouse.[1] Brugse Zot (The Fool of Bruges) comes in several varieties. Its blonde is slightly bitter, with hints of nuts and citrus.

[1] M. Schmidt, Etymologie Der Geografischen Beinamen (Books on Demand, 2023), 63.

[1] Georges Rodenbach and Christian Berg, Bruges-la-Morte: roman (Bruxelles: Espace Nord, 2016), 169–86.

[2] J. A. Van Houtte, ‘The Rise and Decline of the Market of Bruges’, The Economic History Review 19, no. 1 (1966): 30–39.

[3] Brecht Dewilde et al., ‘“So One Would Notice the Good Navigability”’, Urban History 45, no. 1 (February 2018): 6.

[4] R.M. Rilke, Neue Gedichte (Im Insel-Verlag, 1907), 78. An estaminet is a tavern.

Leave a Reply