In 1637, an Italian monk by the name of Fulgentius Micanzio wrote an acquaintance who was considering purchasing a violin. On the advice of an expert, Micanzio could assure his correspondent that the best instruments were to be found in the city of Cremona. What makes this letter so particularly interesting is that the expert in question was Claudio Monteverdi, while the interested buyer was none other than Galileo Galilei. The superior violins in question must have been those of the Amati family, as of yet unrivalled in the field. It is testimony both to the artistic and scientific vibrancy of seventeenth-century Italy, and the close-knit, almost provincial nature of its intellectual community, that one letter should tie together the inventor of the modern opera, the father of modern cosmology, and the family that created the modern violin.[1]

The city of Cremona lies by the banks of the River Po, in the middle of that vast, featureless Padanian plain stretching from Milan through Bologna to the Adriatic. It was founded by the Romans in 218 BC, just as Hannibal was crossing the Alps to invade the peninsula in the Second Punic War. Though violins made it famous, it was farming and textiles that made the city wealthy.[2] This wealth can be seen expressed in the magnificent cathedral with its imposing bell tower. Sitting under the portico of the town hall on the opposite side of the cathedral square, one cannot help but feel a tranquil harmony as the setting sun turns the marble of the Romanesque façade a pinkish red.

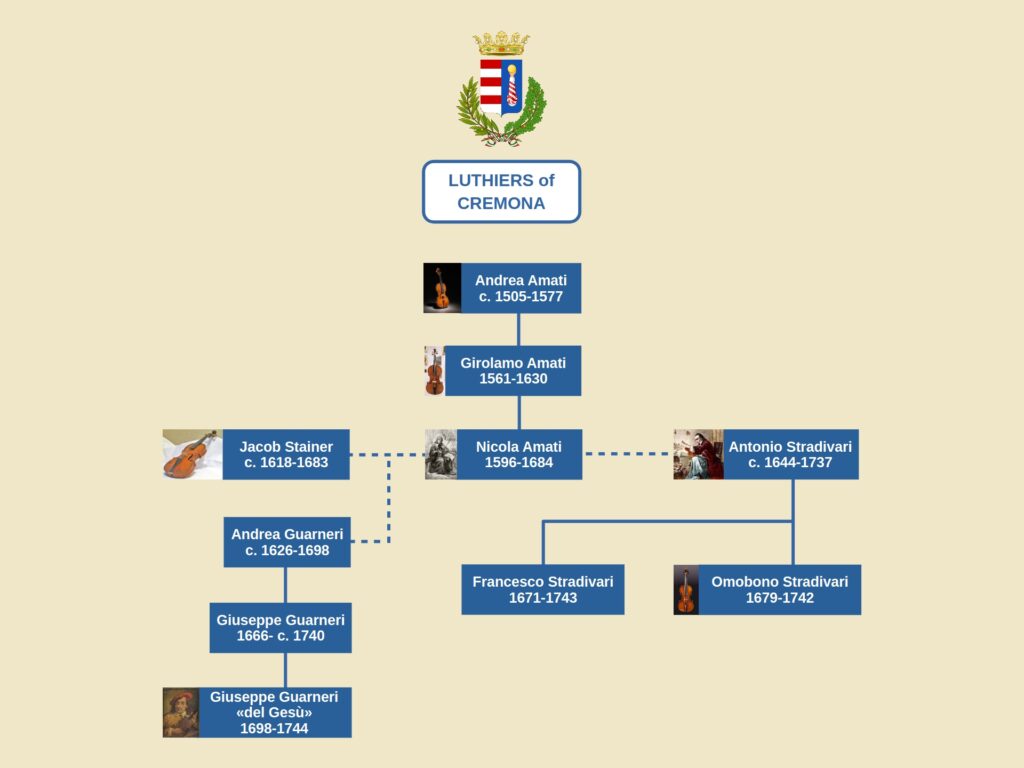

The oldest violins surviving today were made in the 1560s for King Charles IX of France by the Cremonese violin maker – or luthier – Andrea Amati. Over the following decades, the violin business flourished in the city, but famine and plague around the year 1630 wiped out more than half the population. Nicola Amati, Andrea’s grandson, seems to have been the only master luthier left in Cremona, and he was forced to take in apprentices from outside the family. These included Andrea Guarneri, whose family would eventually rival the Amatis themselves, and the Tyrolian Jacob Stainer.

Antonio Stradivari was probably an apprentice of Nicola Amati when he made his first violin in 1666.[3] His production remained low, however, as he struggled for years with developing the Amati style he had inherited. Increasingly, violins were used as solo instruments rather than just for accompaniment to singers, and a stronger, more forceful sound was needed than the rather delicate Amati tune. Years of experimentation with size and shape culminated in 1700: the start of what is considered Stradivari’s “golden period”. The following years saw a prodigious output of the greatest instruments the world has ever seen, culminating in 1716 with the violin called the Messiah. Displayed in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, it is the only Stradivarius considered “as new”, and is today never played. From 1720 until his death in 1737 – at the age of ninety-three – the quality of his work declined somewhat, probably more as a result of inferior material than failing abilities.

Stradivari did not only leave behind a great number of instruments, some 650 of which survive today, he also passed on the moulds he used for construction. If you are making a high-quality, hand-made violin, you could model it on one by Giuseppe Guarneri “del Gesù” – Andrea’s grandson. Most violins today, however, are modelled on those of Antonio Stradivari. And the work is meticulous. There is the neck, ending in the exquisitely crafted scroll, and covered by the ebony fingerboard. There is the bridge on which the strings rest, and the thin, wooden ribs fitted around the mould into the characteristic violin shape.

But the most gruelling work comes with the back and top plates, the pieces that form the violin’s soundbox. These boards are normally made by two adjoining pieces glued together, creating a symmetrical pattern. The back plate can be made from a number of different woods, though maple is normally preferred. The top plate, however, is always made from spruce. Light and elastic, yet strong, it has acoustic qualities like no other material, and is the most important part of any violin. These plates must now be arched down to their exact shapes; the thickness will in places be less than three millimetres, and precision is down to tenths of a millimetre.[4] This is a frustratingly lonely and patience-draining job, where a single instrument can demand more than a month’s undivided attention. At any point one might make the smallest mistake, and the instrument, even if it can be salvaged, must now be sold at a reduced price.

But let us say you finish your violin. You have cut the f-holes into the top plate, strengthened the edges with purfling and applied the varnish that adds both to the look and sound of the instrument. You have now produced a beautiful violin on the exact model of a Stradivarius. And yet, to an expert ear, it will sound nothing like the original. There has been much debate over what gives a Strad its unique and inimitable sound. Though both magic and demonic pacts have been suggested, most today attribute it to the special varnish, the recipe for which today is lost.

Each surviving Strad is valued for its own particular qualities, and given names, often after an early owner in its long pedigree. Whenever one turns up on auction, it is likely to fetch sums in the millions. Since few performers can afford such prices, the violins are often purchased by individuals or establishments with money to spare, and given out on loan to those who know how to play them. The violin pictured above, for instance, carries the name “Cremonese”, possibly from its original label reading “Antonius Stradivarius Cremonensis faciebat anno 1715” – Antonio Stradivari of Cremona made this in the year 1715. It is, however, most famous for its association with Joseph Joachim, Brahms’ collaborator and one of the greatest violinists of his age. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of his career, a group of English supporters presented him with the violin in 1889. Musicians develop deeply personal relationships to their instruments, and speak of them as if they were sentient creatures. Anne-Sophie Mutter – perhaps the most prominent violinist working today, and one fortunate enough to be able to afford her own instrument – talks of her 1710 Lord Dunn–Raven as having a “tiger-like quality”.[5]

Anyone not an expert, however, while being completely honest, will have a hard time understanding what all the fuss is about. Even someone who appreciates violin music may have a sneaking suspicion that this ability to distinguish between individual instruments is little more than pretention. It may therefore come as vindication to find that scientific research seems to confirm just this. A 2017 study had experienced violinists blind test several Strads and new instruments in front of audiences. Neither players nor listeners were able to distinguish between the two, but actually showed a preference for the new ones. It seems then that, as the researchers suggested, “the debate about old vs. new can perhaps be laid aside now”.[6]

Or can it? Another famous blind test may be instructive here. Starting in 1975, PepsiCo conducted a series of experiments where they let test panels sample their own product next to Coca-Cola, and proudly announced that the majority preferred Pepsi. The message was clear: people drank Coke out of old habit, since it was the market leader, while the underdog Pepsi was in fact the superior product. Pepsi, though, has a distinctly sweeter taste than Coke. When test subjects drank the small shot glasses they were given, the sweetest drink was naturally more conspicuous, but when consuming a full-size beverage, more consumers would probably have preferred the more balanced taste of Coke.[7]

This is what researchers refer to as low ecological validity: when the controlled conditions of an experiment do not reflect reality in any meaningful way. The same could be said for the blind Stradivarius sessions. For one thing, virtuosos do not play blind; they play an instrument they have spent years getting to know and master. For this reason, great players are not particularly impressed by the results of experiments such as the above. Maybe the best-known classical performer alive today, Yo-Yo Ma, plays a Stradivarius cello: the 1712 Davidov. According to Ma, he needed about two months to learn how to play the instrument. He points out, however, that “there is no room for error as one cannot push the sound, rather it needs to be released. I had to learn not to be seduced by the sheer beauty of the sound in my mind before trying to coax it from the cello.” For this same reason, the instrument’s previous steward, Jacqueline du Pré, never valued to cello as highly as Ma does, since her far more violently energetic playing style was ill-suited for the instrument.[8]

But regardless of the comparative merits of old and new instruments, we should not forget that each of these newer ones is an exact copy of a centuries-old model. This was a model created by Andrea Amati in the mid-sixteenth century, and perfected by Antoni Stradivari a century and a half later. Such a claim could not be made for any other instrument, where modifications and innovations have continued throughout this period. It is indeed difficult to think of any technology where progress simply ended over three centuries ago. Not only this, but the violin represents the perfect union of functionality and aesthetics. Its forms are often described in almost sensual terms, and yet there is hardly a feature that does not serve a strictly functional purpose for sound production or playing technique. The words of the English polymath Edward Heron-Allen are as valid today as when he wrote them in 1884:

It is a matter of considerable astonishment to many persons that the fiddle took its present familiar shape, apparently quite suddenly in the sixteenth century, and, in spite of all attempts to change it, and in spite of all experiments made with a view of introducing other forms, has kept it ever since.[9]

In short, making the perfect instrument is both the simplest and the most difficult thing in the world.

Menabrea

With its history of extreme political fragmentation, Italy has a tradition of fierce regional rivalry and animosity. Often the closer two towns are, the more acrimonious their relationship. This kind of local patriotism has a name in Italian: campanilismo, from the citizen’s attachment to their campanile, or bell tower. The term supposedly originated with two small towns in the southern region of Campania. When one of these towns built the tower of their church, so the story goes, they deliberately constructed its east side without a clock, so that the townsfolks in that direction would not be able to tell the time.

If local pride is based on one’s bell tower, then the Cremonese should have a lot of it. The tower of their cathedral, the so-called Torrazzo, is the tallest brickwork bell tower in Italy, and the third tallest in the world. It soars imposingly over the adjoining Piazza del Comune, and indeed over the city itself.

In business since 1846, Menabrea claims to be the oldest brewery in Italy, though its year of foundation is the same as that of Peroni. It is brewed in Biella in Piemonte, north of Torino. Their bionda has that distinctive Italian sweet corn taste, but also significant bitterness, with perhaps a hint of strawberry.

[1] Toby Faber, Stradivarius: One Cello, Five Violins and a Genius (London: Pan Books, 2005), 24–5.

[2] Stewart Pollens, Stradivari (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 3.

[3] William Henry Hill, Antonio Stradivari, His Life and Work (1644-1737) (London: Macmillan and Co., 1909), 27‑9.

[4] Juliet R. V. Barker, Violin-Making: A Practical Guide (Ramsbury: Crowood Press, 2007), 37–56.

[5] ‘Anne-Sophie Mutter: The Big Picture’, The Strad, April 2020, 28–35.

[6] Claudia Fritz et al., ‘Listener Evaluations of New and Old Italian Violins’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, no. 21 (23 May 2017): 5400.

[7] Malcolm Gladwell, Blink: The Power of Thinking without Thinking (London: Penguin Books, 2006), 158–9.

[8] Faber, Stradivarius, 222–26, quote on 8.

[9] Edward Heron-Allen, Violin-Making (London: Ward, Lock, & Co., 1885), 125.