In Denmark, there is a story about the villagers of Mols in Jutland. Fearing that war was about to break out in the country, they decided to hide their most treasured possession: the church bell. A handful of men set out to sea in a rowboat to sink the bell, where it could be retrieved when the danger had passed. Once the bell had been submerged, however, one of the villagers wondered how they would be able to find it when that time came. This was when the cleverest among them had a brilliant idea: pulling out his knife he made a notch in the side of the boat on the spot where the bell had been dropped; that way they would know exactly where to look.

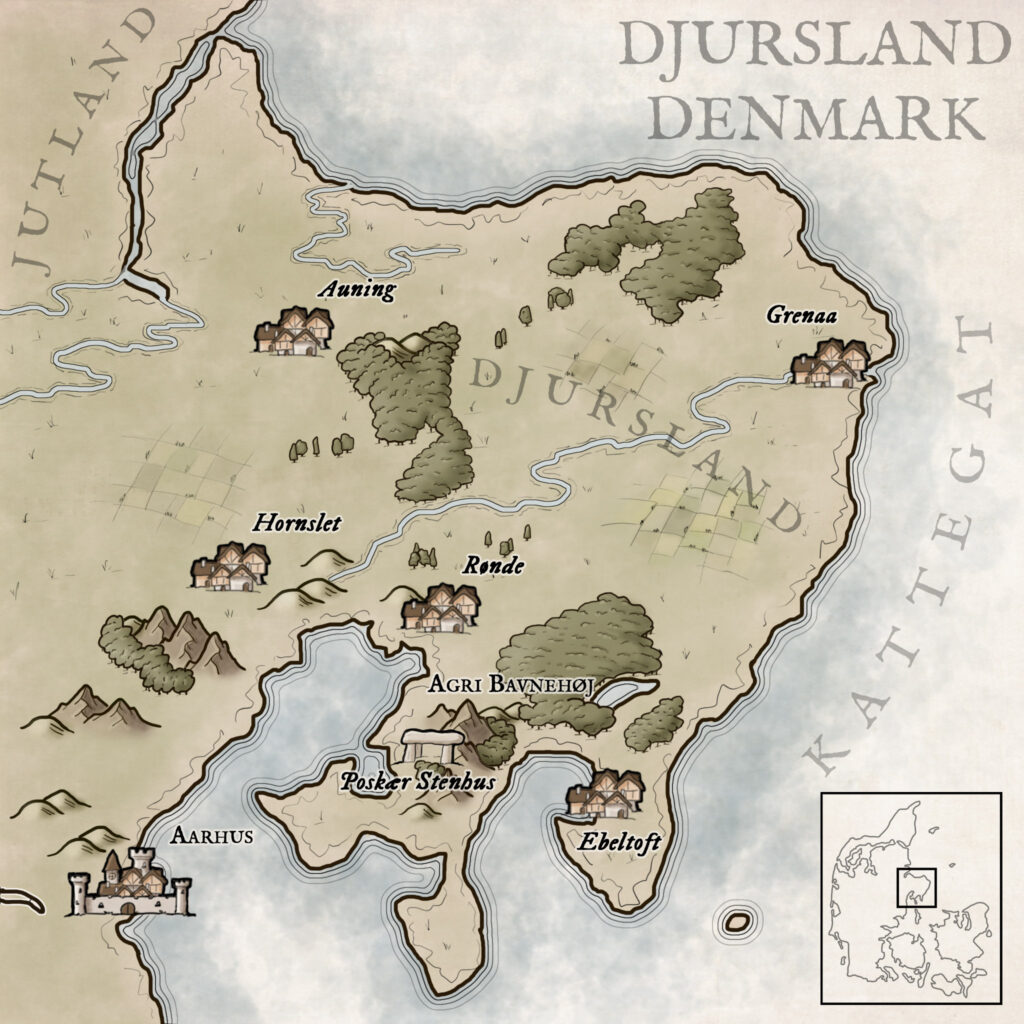

The landscape of Mols makes up the southern part of Djursland, the nose-like appendage to eastern Denmark. It is surprisingly hilly for the mostly flat nation, though its highest point, Agri Bavnehøj, rises to a mere 137 metres. More characteristic of Denmark, its roads are perfectly adapted to cycling. Farmsteads and villages with half-timbered houses lie scattered among swelling cornfields. In the forests – today protected as national park area – hares, deer and other wildlife can be seen. Whitewashed churches look out over sandy beaches in scenery that appears almost Mediterranean in summer. An excellent tourist destination, Mols is nevertheless famous primarily for one thing: popular anecdotes about the immeasurable stupidity of its inhabitants – the so-called Molbo stories.

Such stories are sometimes referred to as blasons populaires, a term coined by the French historian Alfred Canel in his 1859 book Blason populaire de la Normandie. Canel concerned himself primarily with proverbs, but the term has since come mostly to denote stories, jokes or clichés that highlight the particularities – often of a negative sort – of a group of people.[1] All European countries offer their own versions. Some of the blasons are about other, neighbouring countries: the Spanish about the Portuguese, the English about their Celtic neighbours, and more or less everyone about the Belgians.[2]

Most commonly, however, we are talking about regional stereotypes within a single nation. These are not – or not normally – ethnic slurs. For the most part, the jokes are made in harmless fun; the targets belong to the same ethnic or language group as the teller, and more often than not they will eagerly embrace the stories themselves. A popular variety in Ireland is the so-called Kerryman joke – mostly just recycled versions of jokes the English tell about Irishmen. Some varieties, though, take on a somewhat darker hue. In England, the inhabitants of East Anglia are often described as given to inbreeding, while the Welsh are similarly described as disposed towards bestiality.

Mols, Normandy, Kerry, East Anglia, Wales – what do these places have in common? They can all, in part or in whole, be considered peninsulas, as they are surrounded on three parts by water. Mols is in fact a peninsula on a peninsula on a peninsula (see map). These are places people do not simply pass through; no one goes there unless they have a special purpose for doing so. As a consequence, they are less likely to develop transportation hubs, or major centres of commerce, administration or culture. The dominant livelihood will be agriculture or fishing. Hence, they gain a reputation for being backward, stupid, stingy, lazy, sexually perverted. In more mountainous countries, the main arteries will pass along the coast, and the least developed regions will be inland, in the narrow, inaccessible valleys. In Norway, the valley of Setesdal gave its name to a disease known as Setesdalsrykkja, or the Setesdal twitch. The condition (in fact Huntington’s disease) was in the popular association attributed to inbreeding in the sparsely populated valleys, further stigmatising sufferers.[3]

For better or worse, the phenomenon must be understood as a core-periphery dynamic. Under this model, cities evolve at the core of a population network as centres of commerce and manufacture, while the periphery consists of rural areas dominated by agriculture. From this emerges a hierarchy – formally or informally – where the core ranks higher than the periphery in terms of wealth, education and status.[4] These differences can manifest themselves socially through feelings of superiority or inferiority. As for the Molbo stories, it is interesting to note that they originated in Aarhus, the city just across the bay from Mols, and easily visible from Agri Bavnehøj. The first such stories were published in 1780, when Aarhus prospered as a centre of trade, and the genre grew in popularity throughout the nineteenth century, as the city industrialised. To the townspeople, the outlying villages must have appeared more and more like a foreign country. Moreover, as denizens of Denmark’s second city, Aarhusianers may have compensated for a certain status anxiety in the face of the far more metropolitan Copenhageners, who in turn have been known to make jokes at their expense.

The contempt, however, went both ways. Seen from the periphery, it was not only the – often unearned – arrogance of the centre that was aggravating, but large cities were also associated with taxation, military recruitment and other forms of burdensome administrative intrusion. Furthermore, even though city life offered obvious advancement opportunities, these were for the few. For the vast majority, urban life was a dreary affair. Cities were noisy, smelly, dirty and crowded. The pollution and crowding created ideal breeding grounds for contagious diseases, and as a result, life expectancy tended to be lower.[5] Moving to the cities was rarely a choice for those with other options, and not for nothing did the wealthy go down to their country estate whenever the chance offered. Under these circumstances, is ridicule not bearable, even desirable? Who would not, as that famous Dane once put it, bear “the proud man’s contumely”, welcome it even?

Tales of the Wise Men of Gotham are similar to the Molbo stories: humorous anecdotes about the foolishness of the inhabitants of a small village in England. But the alleged origin of the stories adds an extra dimension to the narrative. Legend has it King John was coming to Gotham, and the locals did not want to bear the expenses associated with a royal visitation. They came up with a plan whereby they would act mad, so that the royal household might pass by. Their activities included building a fence to contain birds and trying to drown an eel: story elements not much different from their Danish equivalents. The king did indeed change his itinerary.[6]

This is not to say that all blasons populaires have their origin in rural intransigence, but the story nevertheless reflects the mutual distrust often underpinning the centre-periphery dynamic. In the story about the church bell, the solution may have been absurd, but the concern was realistic enough. If we assume the event took place in the days of the Napoleonic wars, an invasion of Denmark was far from improbable. Under such circumstances, invaders often appropriated church bells to melt the metal into weaponry.

In another Molbo story, the king was visiting the region, and the locals were unsure about how to behave in the royal presence. The mayor told them not to worry; if they followed his lead, everything would be fine. As the king’s procession passed, the mayor bowed low, but as he did so his suspenders broke, and his trousers fell down. The villagers obediently followed suit, and dropped their trousers to the ground.

In a story such as this, it is hard to say exactly who the butt of the joke is.

Ceres

There were farmers in Denmark long before there were cities – agriculture arrived here around 4,000 B.C. A few centuries after this, people began constructing megalithic structures like the one called Poskær Stenhus, built around 3,300 B.C. It is what is known as a round barrow, and is the largest of its kind in Denmark. The last ice age had deposited numerous giant rocks across the fields of southern Scandinavia, some of which were used for structures like this. The capstone at the top has been shown to be one half of a larger stone, where the other half was used for a similar barrow a couple of kilometres away. Whether the rock split naturally or it was done by the builders, we do not know. It is natural to assume that these early farmers used the site for some sort of fertility rites, but we know nothing of their ceremonies, nor the names of their gods.[1]

We do know that the Roman goddess of grains was called Ceres, and that this is therefore an excellent name for a beer. Ceres brewery was founded in Arhus in 1856. Though it ceased operations in 2008, its Top Pilsner is still brewed elsewhere, but it can be hard to find, even locally. Unlike better known Danish beers, like Carlsberg, it has a more distinct bitter, acerbic quality.

[1] Palle Eriksen, Poskær Stenhus: myter og virkelighed (Højbjerg: Moesgård Museum, 2000), 77–85.

[1] Canel, A., Blason Populaire de La Normandie, 2 vols (Rouen: Lebrument, 1859), i-iv.

[2] Romain Seignovert, ed., De qui se moque-t-on?: tour d’Europe en 345 blagues (Paris: Les Éditions de l’Opportun, 2016), introduction.

[3] Alf L. Ørbeck, Setesdalsrykka (Chorea Progressiva Hereditaria) (Oslo, 1954), 13–14.

[4] Michael Storper and Allen J. Scott, ‘Industrialization and Regional Development’, in Pathways to Industrialization and Regional Development (Taylor and Francis, 2020), 3.

[5] Catalina Torres, ‘Exploring the Urban Penalty in Life Expectancy During the Health Transition in Denmark, 1850–1910’, Population Vol. 76, no. 3 (23 December 2021): 417.

[6] Graham Seal, Encyclopedia of Folk Heroes (Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2001), 272–73.